The Craft and the Klan

by Paul A. Fisher

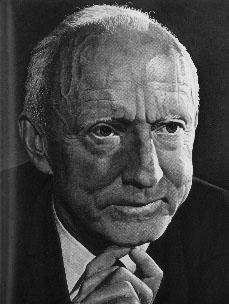

Hugo Lafayette Black - U.S. Supreme Court Justice, U.S. Senator, KKK Klansman, Freemason

A Tombstone becomes a Stepping Stone

The kindly and beloved 48-year-old priest, a native of Athlone, Ireland, had

been pastor of St. Paul's Catholic Church for 17 years when he died from a gunshot

wound, inflicted by an impoverished Methodist minister-barber, as he sat reading

after dinner on the front port of his old frame rectory.

Father Coyle's murderer, Rev. E.R. Stephenson, was assigned no regular church, but

usually hung around the courthouse looking for couples to marry. He was referred to

as "the marrying parson" by courthouse habitues.

A local newspaper said the minister was angry with the priest because Stephenson's daughter

Ruth was considering conversion to Catholicism, and was planning to marry Pedro Gussman,

a Catholic Puerto Rican who was 12 years older than the young woman.

Stephenson admitted that he had called the priest "a dirty dog," but said Father Coyle

"struck me twice on the head and knocked me to my knees." At that point the parson

said the priest "run his hand in his pocket, and I shot."

Two hours after the murder, Ruth Stephenson telephoned here mother to announce her

marriage to Gussman.

On August 13, the minister was formally charged with murder in the first degree. On

that day and the following day the press surprisedly reported that the impoverished

defendent had conferred with a number of local attorneys, but had made no announcement

concerning the selection of a specific lawyer.

It is doubtful that many readers of the local papers at that time would have

paid particular attention to a headline in the Birmingham Age-Herald which

appeared immediately under a photograph of mourners attending Father Coyle's funeral.

The headline said: "Masons To Hold Conference." The brief news item noted that the

Jefferson County Masons would hold their semi-annual meeting August 16-17.

Meanwhile, at the priest's funeral Mass, Bishop Edward P. Allen of Mobile deplored

the dramatic change that had taken place in Birmingham during the past several years.

Twenty-five years earlier, and up until 1915, he said, non-Catholics had always been

cordial, broadminded, and got along well with their fellow Catholic friends and

and neighbors.

However, all that had changed, and he attributed the new attitude to the work of

politicians and secret societies.

The year 1915, of course, markd the resuscitation of Ku Klux Klan by Col. William

Simmons.

On August 14, Ruth Stephenson Gussman, the new bride, informed the press that she

had been baptized into the Catholic Church at Our Lady of Sorrows Church by Father

Kelly - not Father Coyle.

She also said her father had locked her in her room on the day she was scheduled

to received her First Communion. Additionally, she told the press that her parents

were trying to force her to marry "a Mason who was divorced."

On August 16, the new bride's father, who, it was universally agreed, was of

very modest circumstances, announced that he had selected, not one attorney,

but had engaged a battery of four lawyers. They were: Hugo Black, Crampton Harris,

John C. Arnold and Fred Fite.

- Behind the Lodge Door, by Paul A. Fisher

|

Indeed, it is remarkable that after three months' investigation by one of the nation's major newspapers, the 21-part series made no mention of the close bond between the Klan and Freemasonry.

After all, most of the Klan's major leaders were Freemasons. The organization's founder, Col. Simmons, was a Mason, and a Knight Templar. Also, C. Anderson Wright, King Kleagle of the New York Klan and chief of staff of a Klan group known as Knights of the Air, was a 32nd degree Mason. Dr. Hiram Evans, who succeeded Simmons as Imperial Wizard, "for many years...was recognized as one of the most active men in Masonry, and is a 32nd degree Knight Commander of the Court of Honor...[who] had been devoting almost his entire time to Scottish Rite Masonry at the time the Klan was organized..."

Israel Zangwill, a prominent London author, said he was told that Dr. Evans had performed inductions into the 32nd degree of the Masonic order.[28]

Further, initiations were held "in the Masonic Temple in New York City," and the Klan shared office space in Beaumont, Texas "with the secretary of the Grotto, which, in a way, is a Masonic organization"[29]

Edward Young Clarke, a former publicity agent and fund raiser, who became Imperial Kleagle (salesman) for the Klan, "realized the value of representing the Klan to be 'the fighting brother' of Masonry." Consequently, he issued orders that "none but men with Masonic affiliations" should be employed as Kleagles in the Klan's nationwide sales network.

Accordingly, he established the Great American Fraternity (GAF) in Georgia in 1920 as a nationwide sales organization composed of members of 13 secret societies believed to be hostile to the Catholic Church. Klan salesmen were instructed "in selling effective political anti-Catholicism to their brothers in their respective lodges."

Members of the GAF included the Freemasons, Junior Order of United American Mechanics, Independent Order of Odd Fellows, guardians of Liberty, Order of the Eastern Star, Daughters of America, Rebekkahs, the Loyal Orange Institution, Knights of Luther, National League of Pathfinders, and the Order of De Molay.[30]

Although some Masonic spokesman condemned the Klan, there were very few Masonic leaders who shared that view.

Charles P. Sweeney, writing in The Nation magazine in 1920, said that if responsible Masons "exerted a tithe of the influence they possess, [they] could do more to stop Know-Nothing program than any other single force."[31]

Imperial Wizard Simmons denid the authenticity of a report that the Masonic leadership in Missouri had condemned the Klan in 1920. He said he had addressed 3,500 people in the Shrine Temple at St. Louis in September of that year, and learned that the alleged Masonic condemnation "has been strongly denied."[32]

The Minneapolis Daily Star reported that most Klansmen in the city were Masons, while the State leaders included many popular Shriners.

In Wisconsin, the Klan leader was William Wiesemann, "a local insurance man who was prominent in Masonic circles."

Klan advertisements read: "Masons Preferred," and many Masonss joined, as did a number of Milwaukee Socialists.

A New York Klansman claimed that 75 percent of the Klan enrollment in that State were Masons.

In Oregon, both Fred L. Gifford, head of the Klan in that State, and his secretary, Frank Parker, were Masons. Delegates of an Oregon Klan front, the Good Government League, were Masons, Orangemen, Odd Fellows and Pythians.[34]

In 1924, an editorial in the Scottish New Age magazine said the Rite holds "no brief for or against any organization outside of the Scottish Rite," and added the following observation: If Freemasonry follows the traditions of centuries, it "cannot dictate to any Mason what shall or shall not be his affiliations outside the lodge..."

The editorial then invited attention to a letter by the editor of the Masonic Herald that had appeared in The New York Times on August 28, 1923. The letter said "genuine Masons - Masons who are such in their hearts - cannot be Klansmen, and connot welcome with true brotherly love Klansmen into their lodges."

Commenting on the Herald editor's letter, the New Age said: "Possibly the edtor of the Masonic Herald is prejudiced, but no Masonic editor has any more right to speak pontifically for the Masonic fraternity than [a Catholic Priest]."[35]

An article in the same publication commented: "One may not subscribe to the Ku Klux Klan platforms in toto, but one may say of these and similar anti-Catholic movements...this fellow hath the right sow by the ear."[36]

Although most dcent citizens were outraged by the Klans's rampant bigotry, none of the Craft's Grand Lodges had taken "official action in regard to the Klan."[37]

Nationally, "attacks on Masonry" in Italy "fired the Klan to renewed action and increased [its] membership."[38]

The above history strongly indicates that the Klan was a Masonic front group. Certainly the Klan's venomous war on Catholics was in keeping with a long tradition generally associated with the Masonic fraternity.

The Klan In Action

* A sheriff in Waco, Texas, who stopped a parade of masked men and demanded the names of the marchers, was shot and removed from office in proceedings "sponsored by the most influential citizens of his county."The free publicity given to such a militant anti-Catholic organization by The World's widely publicized articles, coupled with Imperial Wizard Simmon's testimony before the House Rules Committee only served to advance the rapid growth of the Klan.*In Birmingham, Alabama, a "Klansman" who had killed a Catholic priest in cold blood on his own doorstep "was acquitted at the 'trial' amidst the plaudits of the mob."

*In Atlanta, Georgia, members of the Board of Education received letters threatening their lives when they hesitated to consider a resolution to dismiss all Catholic public school teachers.

* In Naperville, Illinois, a Catholic church was destroyed by fire two hours after a monster midnight Klan initiation in the neighborhood

*Imperial Wizard Simmons made clear that the Klan had "given the world the open Bible, the little red school house, if you please, the great public school system."[39]

Simmons whetted the insatiable anti-Catholic appetite when he told the Committee there was available to the Klan "possibly the greatest existing mass of data and material against the Roman Catholics and Knights of Columbus." The material included "affidavits and other personal testimony attributing to the Roman Catholics and the Knights of Columbus in America more outrages and crimes than the Klan has ever been charges with."

At the time the House Rules Committee hearings were underway, a resolution to investigate "each and every secret order in the United States." Ten days later the Committee called off further investigation of the Klan.[41]

Typical of Klan techniques in the North, in 1922, was an incident at Elizabeth, New Jersey. Five Klansmen marched into the Third Presbyterian Church an handed the pastor an envelope in which was enclosed a note and $25. The note expressed "appreciation" for the way the deacon's fund was administered by the church, and asserted that the Klan stood for "white supremacy, protection of women...and seperation of church and state."

Five days later, the church's pastor, Rev. Robert W. Mark, preached a sermon attacking the Knights of Columbus. He remarked that if he had to choose between joining the K. of C. and the Ku Klux Klan, he would select the Klan.

Rev. Mark said God intended the white race for leadership, but that he (Mark) did not advocate suppression of any race. With those words, he invited Rev. C.J. Turner, Negro pastor of the Siloam Presbyterian Church, who was sitting in the front row, to join him on the platform. The two ministers stood side by side singing "America".[42]

Cathophobia (or morbid fear and hatred of the Catholic Church) was rapidly spreading across the nation. In November, 1923, for example, Lowell Mellett, a nationally prominent journalist, writing in the prestigious Atlantic Monthly magazine, recalled stories circulated during his boyhood in Indiana which alleged that Catholic youths were trained "to seize the whole country." The same stories were rampant he said, when he returned to his hometown 30 years later.[43]

Mellet said the Klan was charged with being opposed to Jews, Negroes and Catholics; however, he had heard "little concerning Jews and Negroes," but "heard much concerning the Catholics." He added: "Very clearly, the crux of the Klan problem in Indiana is the Catholic Church."[44]

Some of Mellet's old friends, whom he characterized as "just some of the best citizens of Indiana," were Klansmen. They joined, he said, because they believed the Vatican "is soon to be moved to Washington D.C.," and because they opposed the "fixed policy of the Church to keep its members to a definite level of ignorance."[45]

One of the most serious charges against the Church, he remarked, is that it "is endeavoring to obtain control of the public schools."[46]

He charged that newspapers "have feared the Catholic Church," and agreed that that was an article of Klan faith which "has a real basis."[47]

Mellet's answer to the Klan's problem with the Church was to investigate, not the Klan nor other secret societies which were viciously attacking the Church and her adherents, but rather to investigate the Church. Catholic churches, he said, should "be forced open" to prove or disprove allegations "of buried rifles and ammunition."[48]

If adopted, that proposal, and a similar outrageous suggestion by Mellett, would have trampled the most basic religious and civil rights of Catholics.

His other suggestion was that a commission of inquiry be established to "call publically for the presentation of every charge against the Catholic Church that any responsible person or group of persons might have to make, and then investigate the truth of these charges."[49]

Nowhere in the article did Mellett furnish evidence to support wanton Klan charges. Presumably, this outrageous assault on the rights of citizens was warranted merely because a group of friends, "just some of the best citizens in Indiana," thought it would be nice.

Curiously, he never suggested an assault upon the Klan or Freemasonry. In fact, he explicitly said the Klan and secret societies should not be investigated. The reality was, however, that abundant evidence had been presented over the years which detailed the serious danger emanating from both the Klan and Freemasonry.

Indeed, in the same issue of the Atlantic Monthly in which Mellett's article appeared, there was a lettter from "A Citizen of Oklahoma" who said the State was under the "secret rule of a hidden clique." He noted that the civil offices of the State "are unquestionably in the hands of the Klan; and that fact makes it impossible for the Governor to oust these officials."

In that regard, the unidentified letter writer observed that the Governor was being considered for impeachment by the Klan and its many sympathizers. The Klan, he remarked, "is the most dangerous force at large in the country today."[50]

Strangely, however, Lowell Mellett was convinced that the Roman Catholic Church was far more dangerous than the Klan.

About the Author

Paul A. Fisher graduated from the University of Notre Dame and subsequently attended

Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and the American University in

Washington, D.C. He served in the Army with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during

World War II in North Africa and Italy, and later he was called into service by the Army

to serve as a Counterintelligence Officer in Korea during the conflict in that country.

For eight years he was legislative and press aide to Congressman James J. Delaney (D., NY),

and later, on seperate occasions, was Washington correspondent for Triumph Magazine,

the National Catholic Register, Twin Circle Magazine and The Wanderer, a

national Catholic weekly newspaper.

Paul A. Fisher graduated from the University of Notre Dame and subsequently attended

Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and the American University in

Washington, D.C. He served in the Army with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during

World War II in North Africa and Italy, and later he was called into service by the Army

to serve as a Counterintelligence Officer in Korea during the conflict in that country.

For eight years he was legislative and press aide to Congressman James J. Delaney (D., NY),

and later, on seperate occasions, was Washington correspondent for Triumph Magazine,

the National Catholic Register, Twin Circle Magazine and The Wanderer, a

national Catholic weekly newspaper.

Notes:

28. U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Rules, 67th Congress, Hearings on the Ku Klux Klan, October 12, 1921, published as Mass Violence in America, New York, The Arno Press and The New York Times, 1969, pp. 37, 23.

The quotation concerning Evans' Masonic activity appears in The Fortnightly Review, October 1, 1925, p. 401.

Israel Zangwell's statement is attributed to Rev. Ed. Albrecht of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and appears in Theodore C. Graebner's A Handbook Of Organizations, St. Louis, Missori, Concordia Publishing House, 1924, p. 192.

29. U.S. House Rules Hearings, pp. 19, 72.

30. Charles P. Sweeney, "The Great Bigotry Merger," The Nation, July 5, 1923. p. 10.

31. Ibid

32. U.S. House Rules Hearings, p. 75.

33. David M. Chalmers, Hooded Americanism, The First Century of the Ku Klux Klan, Garden City, New York, Doubleday and Co., 1965, p. 149 (on Minneapolis); p. 191 (on Wisconsin); and p. 254 (on New York).

34. Lem A. Dever, Masks Off! - Confessions of an Imperial Klansman, 2nd revised ed., Portland Oregon, published by author, 1925, pp. 39, 51.

35. New Age January 4, 1924, p. 43.

36Ibid., John Jay Chapman, "Strikes at the Source," p. 214.

37. New Age, May, 1926, p. 306

38. The New York Times, February 21, 1926, "The Klans Invisible Empire Fading," section 8, p 1.

39. The five incidents cited are found in Sweeney, op. cit., pp. 8, 9.

40. House Rules Committee Hearings, p. 73

41. See The New York Times, October 8, 1921, p. 4; and ibid., October 18, 1921, p. 6.

42. Ibid., May 16, 1922, p. 14; May 21, 1922, p. 14.

43. Lowell Mellet, "Klan and Church," Atlantic Monthly, November, 1923, p. 586.

44. Ibid., p. 588

45. Ibid., p. 588, 589

46. Ibid., p. 588

47. Ibid., p. 591

48. Ibid.,

49. Ibid., p. 591-591

50. "A Citizen From Oklahoma" (letter), Atlantic Monthly, November, 1923, p. 720.