We must turn our attention to an ideal that has always been of concern to men aspiring to the regeneration of all mankind - the liberation of the entire world and the establishment of the republic of brotherhood and world peace. Among the many remedies, there is one which we must never forget: the total annihilation of Catholicism and even of Christianity. What we must wait for is a pope suitable to our purposes because with such a pope, we could effectively crush the Rock on which God built his Church. Seek a pope fitting our description. Induce the clergy to march under your banner in the belief that they are marching under the papal banner. Make the younger, secular clergy, and even the religious, receptive to our doctrines.

Grand Master, Grand Orient of France

Grand Master, Grand Orient of Austria

Grand Master, Grand Lodge of Prussia

Grand Master, Grand Orient of Italy

The Permanent Instruction

By, Father Malachi Martin

The death and entombment of the First Polish Republic as a sovereign nation-state was

an accomplished fact by 1795. It was the direct result of pacts for its extinction

concluded between the Great Powers of Europe. It lasted a full 125 years, until

1919, when the Second Polish Republic was established, to live a precarious twenty-five-year

existence until 1939, when, once more, its extinction was accomplished by Hitlerian Germany

and Stalinist Russia, whose avowed aim was to liquidate forever not merely the nation-state

of Poland but the Poles as a distinct ethnic and national group. No other great power in

Europe really objected to that result. As David Lloyd George wrote in a well-publicized

letter of September 28, 1939, "the people of Britain are not prepared to make colossal

sacrifices to restore to power a Polish regime represented by the present government..."

Lloyd George goes on to say that the USSR had every right to swallow up the Polish republic.

The death and entombment of the First Polish Republic as a sovereign nation-state was

an accomplished fact by 1795. It was the direct result of pacts for its extinction

concluded between the Great Powers of Europe. It lasted a full 125 years, until

1919, when the Second Polish Republic was established, to live a precarious twenty-five-year

existence until 1939, when, once more, its extinction was accomplished by Hitlerian Germany

and Stalinist Russia, whose avowed aim was to liquidate forever not merely the nation-state

of Poland but the Poles as a distinct ethnic and national group. No other great power in

Europe really objected to that result. As David Lloyd George wrote in a well-publicized

letter of September 28, 1939, "the people of Britain are not prepared to make colossal

sacrifices to restore to power a Polish regime represented by the present government..."

Lloyd George goes on to say that the USSR had every right to swallow up the Polish republic.

When the Western allies, Great Britain and France, did finally wage real war on Germany, ostensibly to free Poland, manifestly it was because they themselves were faced with a lethal threat. The "phony war" of September 1939 to March 1940 was a time of intensely studied options. It need not have ended with the waging of the real World War II at the beginning of spring 1940.

The "real proof of the pudding" came with the tragically erroneous Yalta and Potsdam agreements between Joseph STalin and the Western allies: Poland was once more condemned to extinction, its people once more to be merged indistinguishably in the "peoples" and the "republics" of the Stalinist Gulag Archipelago - and that for another forty-three years. Another pact of Polish extinction.

Apart from the mortal blow to the rights of Poles as individuals and citizens, however, Poland's planned extinction for a terrible total of 168 years was a geopolitical and historical mistake of universal proportions. Because the net result was a lopsided and unbalanced view of history, of history's models and of history's lessons for later generations, it was a mistake that was doomed to be repeated; and not only in Poland. And despite all its twists and turns and complications, Poland's story from Renaissance times right into our own day makes it clear that the Soviets were by no means the first ideologically driven group to practice the professional elimination of whole blocs of history; nor were they the first to think up the dreadful strategem of the "nonperson" - the person other people agree to pretend never existed.

But this extinction of Poland had one more result of far-reaching consequences: It bred among Poles and particularly in the men and women who were Karol Wojtyla's intellectual, religious and moral mentors and political forebears a vivid realization of geopolitics. For their fate as a nation, their daily lives as a people, and the very reason for being Poles depended on vastly intricate affairs involving the Great Powers of world politics. The raca stanu about which the Poles were and are justifiably preoccupied - the raison d'etre of Poland as a nation-state - has been so long entwined with international affairs and world-wide events that Poland has taken on a permanently geopolitical connotation.

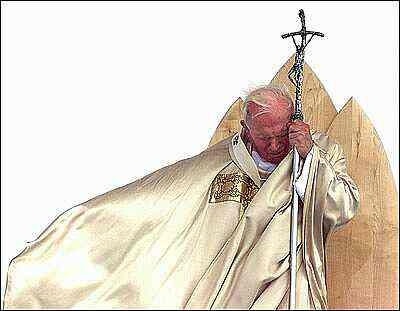

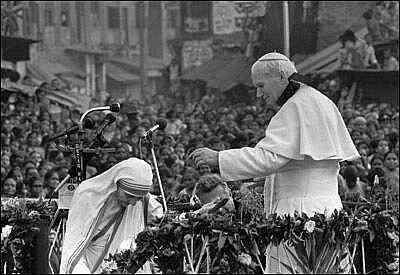

The upper reaches of that connotation and its global dimension was guaranteed by the inherent Romanism of Poland and what it stands for. In a true but not derogatory sense, Poland became and is a regularly played pawn in the geopolitical game. Small wonder then that John Paul would come equipped geopolitically. The Pacts of Extinction ensured that much.

The three major forces that led directly to the demise of the First Polish Republic in 1795 sprang from such varied motives and background that, without the advantage of hindsight, one would have expected ware to break out between them, rather than the fusion of interests that grew instead.

Two of those major forces had their earliest beginnings in the deep and violent strains placed on European order and unity by the relocation of the papacy to Avignon in France for sixty-eight years, from 1309 to 1377; and by the Great Schism that followed for another thirty-nine years, from 1378 to 1417. If ever a door of change opened in the affairs of men and nations, those 108 years constituted such a door.

Until then, the papacy had been the only highly developed and stable institution for hundreds of years, giving to the medieval world a sense of order, unity and purpose. In that world of early Europe, everything - politics, commerce, civil law, legitimate government, art, learning - all depended on the ecclesiastical structure that stretched from pope to cardinals and bishops, priests and monks, and outward through all the ramifications of life.

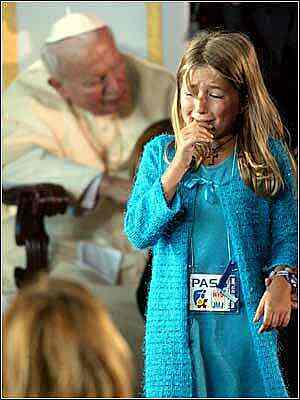

With the Great Schism came a sudden shock of universal doubt as to which of three rival claimants was the valid successor of Peter the Apostle. And along with doubt, the first seeds of challenge to the established order blossomed among the intellectual, artistic and aritstocratic circles of European society. Again, only historical hindsight allows us to see now that, with the Great Schism and the Avignon papacy, something vital had departed from papal Rome, something precious and valuable for the papacy's name and standing. Men, for the first time, started to question papal claims. It was in this context that Catherine of Siena (1347-1380) announced the words she had heard in a vision of Heaven: "The Keys of this Blood will always belong to Peter and all his successors".

The doctrinal revolt of John Wycliffe (1330-1384) in England, imitated and followed by

Jan Hus (1370-1415) and his Hussites in Bohemia, was early warning of the trouble that

was brewing. For on doctrinal bases, such men began to challenge the civil and political

order established on the basis of papal authority.

The doctrinal revolt of John Wycliffe (1330-1384) in England, imitated and followed by

Jan Hus (1370-1415) and his Hussites in Bohemia, was early warning of the trouble that

was brewing. For on doctrinal bases, such men began to challenge the civil and political

order established on the basis of papal authority.

In this climate of uncertainty and challenge that came to mark early-Renaissance Italy, there arose a network of Humanists assocations with aspirations to escape the overall control of that established order. Given aspirations like that, these associations had to exist in the protection of secrecy, as least at their beginnings. But aside from secrecy, these humanist groups were marked by two other main characteristics.

The first was that they were in revolt against the traditional interpretation of the Bible as maintained by the ecclesiastical and civil authorities, and against the philosophical and theological underpinnings provided by the Church for civil and political life.

Given the first characteristic, the second was inevitable: a virulent, professional and confessional opposition to the Roman Catholic Church and,in particular, to the Roman papcy, both as temporal power and as a religous authority.

Not surprisingly given such an animus, these associations had their own conception of the original message of the Bible and of God's revelation. They latched onto what they considered to be an ultrasecret body of knowledge, a gnosis, which they based in part on cultic and occultic strains deriving from North Africa - notably, Egypt - and, in part, on the classical Jewish Kabbala.

The Kabbala, the highest reach of mysticism in Judaism's long history, was a direct descendent of the ancient pre-exilic Jewish mystic tradition rooted in the Carmel figures of Elias and Elisha. It left definite traces in the canonical Jewish Bible - the Assumption of Elias, the Millenarianism of Amos, the Servent Songs of Deutro-Isaiah, the Chariot Visions of Ezekial, the New Covenant prophecies of Jeremiah, the haunting beauty of Malachi's prophecies.

The Jewish Kabbala itself was an attempt to outline how mere mortal man, within the strict Mosaic tradition of God's total seperateness from man, could attain knowledge - and ultimately, possession - of the divinity. For that knowledge, or Kabbala, would itself be possession. Toratic purity was the only preparation for the reception of Kabbala; and it would bring with it profound effects and changes in the material cosmos of man.

The Kabbala was, in other words, a spiritual doctrine about the intervention of the wholly alien and supernatural life of the one God, the Creator of all things, into the materal cosmos.

Whether out of historical ignorance or willfulness or both, the Italian humanists bowlderized the idea of Kabbala almost beyond recognition. They reconstructed the concept of gnosis, and transferred it to a thoroughly this-worldly plane. The special gnosis they sought was a secret knowledge of how to master the blind forces of nature for a sociopolitical purpose.

In the prescientific, pre-Englightenment world, before Francis Bacon "rang the bell that called the wits together," around 1600, that mastery involved, among other things, what is popularly but erroneously called "cabalistic" methods of alchemy - the effort to change the elemental nature of substances, mainly metals. In fact, the dedicated humanist cabalists were always seeking what was called the Philosopher's Stone - a mineral that, by its merest touch, could transmute base metals such as lead into gold.

However, behind all that - behind the cabalists' search for a secret knowledge of the forces of nature, and behind the myth of the Philosophers Stone - lay the yearning to regenerate the world, to eliminate the base or evil forces, and to transmute them into gold of a peace-filled and prosperous human society.

Initiates of those early humanist associations were devotees of the Great Force - the Great Architect of the Cosmos - which they represented under the form of the Sacred Tetrammaton, YHWH, the Jewish symbol for the name of the divinity that was not to be pronounced by mortal lips. They borrowed other symbols - the Pyramid and the All-Seeing Eye - mainly from Egyptian sources.

On such bases as these, the new associations claimed to be the authentic bearers of an ancient tradition that bypassed normative rabbinic Judaism and Christianity alike; a tradition from which both of those religions and sprung but which the cabalists insisted was purer and truer than either of them.

How far these occultist associations might have progessed and what their influence might have been in different historical circumstances must remain an open question. For, as it was, the humanist movement that produced such occult societies found fertile soil among dissidents beyond the Alps. As far as historical researches have gone, it would seem that through the entire swath of Central Europe - from the Alps right up through Switzerland, Austria, Poland, Germany and Scandanavia - there ran the same discontent with the established order, and the same tendency to throw over the dogmas of the Roman papacy in favor of a "more primitive" and, therefore, more faithful interpretation of the Bible events.

Without a doubt, the new secret associations were ready vehicles of that discontent. Over time, in fact, and through an unpredictable series of mergers and mutations, the offspring of these early-Renaissance humanist associations developed into a potent international religious and sociopolitical force that would determine a whole new set of European alliances, and the fate of nations - including the dismal fate that awaited Poland.

For one thing, as they spread northward beyond the Alps, they found adherents

among already existing dissident groups such as the Moravian Brethren of Hussite

origin, the Unitarians and neo-Arians. There was no doubt that revolt was building.

At that climate intensified, the northward spread and acceptance of the occultist

humanists meshed chronologically and most importantly with the beginnings of the Protestant

Reformation in the early 1500s.

For one thing, as they spread northward beyond the Alps, they found adherents

among already existing dissident groups such as the Moravian Brethren of Hussite

origin, the Unitarians and neo-Arians. There was no doubt that revolt was building.

At that climate intensified, the northward spread and acceptance of the occultist

humanists meshed chronologically and most importantly with the beginnings of the Protestant

Reformation in the early 1500s.

As we now know, some of the chief architects of the Reformation - Martin Luther, Philip Melanchthon, Johannes Reuchlin, Jan Amos Kozmensky - belonged to occult societies. And both Fausto and Lelio Sozzini, the Italian anti-Trinitarian theologians, found patronage, funds and a supporting network outside their native Italy. Socinianism, which takes its name from the two Sozzinis, was in fact well received among the brothers of the occult up north in Switzerland, Poland and Germany.

In other northern climes, meanwhile, a far more important union took place, with the humanists. A union that no one could have expected.

In the 1300s, during the time that the cabalist-humanist associations were beginning to find their bearings, there already existed - particularly in England, Scotland and France - medieval guilds of men who worked with ax, chisel and mallet in freestone. Freemasons by trade, and Godfearing in their religion, these were men who fitted perfectly into the hierarchic order of things on which their world rested. In the words of one ancient English Book of Charges, medieval freemasons were required "princypally to loue god and holy chyrche & alle halowis [all saints]."

Freemasons were quite separate from other stoneworkers - from hard hewers, marblers, alabasterers, cowans, raw masons and bricklayers. Freemasons were wage earners who lived a life of mobility and of a certain privlege. They were traveling artisans who moved to the site where they would ply their skills, setting up temporary quarters for their lodging, rest and recreation, and for communal discussions of their trade.

As specialists employed by rich and influential patrons, these artisans of freestone had professional secrets, which they ringed around with guild rules - the "Old Charges" of English and Scottish freemason guilds. That being the case, their lodging, or lodge, was off limits to all but accredited freemasons.

To foil intruders, they developed a sign among themselves - what English freemasons called the "Word" but which might also be a phrase or a sign of the hand - by which to recognize a member who enjoyed the prileges of entry and participation in their lodge.

No one alive in the 1300s could have predicted a merger of minds between freemsaon guilds and the Italian humanists. The traditional faith of the one, and the ideological hostility to both tradition and faith of the other, should have made the two groups about as likely to mix as oil and water.

In the latter half of the 1500s, however, there was a change in the type of man recruited for the freemason guilds. As the number of working or "operative", freemasons diminished progressively, they were replaced by what were called Accepted Masons - gentlemen of leisure, aristocrats, even members of royal families - who lifted ax, chisel and mallet only in the ultrasecret symbolic ceremonies of the lodge, still guarded by the "Charges" and the "Mason Word." The "speculative" mason was born.

The new Masonry shifted away from all allegiance to Roman ecclesiastical Christianity. And again, as for the Italian occultist humanists, the secrecy guaranteed by the tradition of the Lodge was essential in the circumstances.

The two groups had more in common than secrecy, however. From the writings and records of speculative Masonry, it is clear that the central religious tenet became a belief in the Great Architect of the Universe - a figure familiar by now from the influence of Italian humanists, a figure that cannot be identified with the transcendent God who chose the Jewish race as a special people or with the transcendent God of Christian revelation incarnated in Jesus of Nazareth. Rather, the Great Architect was immanent to and essentially a part of the material cosmos, a product of the "enlightend" mind.

There was no conceptual basis by which such a belief could be reconciled with Christianity. For precluded were all such ideas as sin, Hell for punishment and Heaven for reward, an eternally perpetual Sacrfice of the Mass, saints and angels, priest and pope. Indeed, the whole concept of an ecclesiastical organization charged with propagating that Christianity, like the concept of an infallible religious leadership personalized in a pope wielding the irresistible Keys of Petrine authority, was considered to be false and antihuman.

In the inevitable rivalry that would develop between the Catholic and Protestant powers of Europe, the Roman papacy - still a temporal power well into the 1600s - would logically if unwisely take sides, even as the Lodge would associate itself with the Protestant elements involved in burgeoning struggle.

In the midst of all this gathering ferment stood Poland, still foursquare

and vibrant in the strategic heart of Central Europe, and still foursquare

in its fealty to the Holy See of Rome as declared in the Piast Pact. For well

over five centuries, as hereditary monarchy, then as constitutional monarchy

and as Unitary Republic, Poland had been the bulward of Roman Christianity,

and the one military force that halted the onrush of the Ottoman Turks.

In the midst of all this gathering ferment stood Poland, still foursquare

and vibrant in the strategic heart of Central Europe, and still foursquare

in its fealty to the Holy See of Rome as declared in the Piast Pact. For well

over five centuries, as hereditary monarchy, then as constitutional monarchy

and as Unitary Republic, Poland had been the bulward of Roman Christianity,

and the one military force that halted the onrush of the Ottoman Turks.

However, even before her third and final victory under Jan Sobieski, over the Turks at Vienna in 1683, Poland's geopolitical position in Europe had been radically altered by the Protestant Reformation launched over 150 years earlier, in 1517, by Martin Luther. In fact, whatever else it was intended or proved to be, in geopolitical terms the Protestant Reformation was a mega-earthquake. By the time of Sobieski's 1683 triumph over the Turks, Poland was practically surrounded and certainly menaced by a newly Protestant world: Prussia, Sweden, Saxony, Denmark, Transylvania (Protestant Hungary). The enmity of those countries for Poland was shared by other emergent powers in Europe - notably England and Holland, both Protestant nations by then.

In calm retrospect, it seems beyond the shadow of any doubt that one major contributing factor in the demise of the First Polish Republic was the influence - mainly among the Protestant enemies of Poland, but eventually, and to an important degree, within Poland as well - of the now humanist Freemasons.

In the era of Accepted Masonry, membership in the Lodge spread throughout the governing and academic classes in Protestant countries. The great universities of Europe in Germany, Austria, France, Holland and England, as well as the scientific establishments, all provided recruits to the Lodge. European Masonry became, in fact, primarily an organization of aristocrats, large landowners and realtors, bankers and brokers. Princes of the royal blood joined the Lodge in important numbers - George IV of England, Oscar II and Gustav V of Sweden, Frederick the Great of Germany, Christian X of Denmark, to name but a few.

The aim of the cablist humanists had always been sociopolitical change. But with such a membership as it attracted, European Masonry wanted no social revolution. The main aim of European Freemasons was political: to ensure the balance of power in Europe for England, Prussia, Holland and Scandinavia.

The nub of the matter was, however, that any strategic reckoning of these countries, which had been newly reborn as Protestant powers, had to envisage the removal of the First Polish Republic, if their dream of the great northern Protestant alliance was ever to take flesh.

In the 1500s, Poland's eyes for culture, learning, art, thought and philosophy were on Paris. Its sabers were directed to the nascent duchy of Moscow in the east, and to the European Ottoman power to the south. Its heart remained fixed on Rome. Within its own borders, it was a federation of five or six ethnic groups within a republic based on constitutional freedom of religion and worship, which fostered Catholicism, lived at peace with the Protestants in its midst, and provided Jews with legal, religous and civil automomy in a homeland away form their homeland. The country had become militarily strong, economically prosperous, politically mature, culturally advanced.

Geopoliticcally, it was still the strategic plaque tournante of Central Europe. Out of Eruope's total population of 97 million, only France, with a population of 15.5 million, exceeded Poland's 11.5 million. Poland's borders ran from the river Oder, in the west, to 200 kilometers beyond the riverine land of the Dnieper, in the east; and from the Baltic in the north to the river Dniester in the south.

Religiously, meanwhile, Poland was still thoroughly Romanist and papal in its heart, its mind and its allegiance.

As a People, as unitary nation and as a strategic linchpin, Poland therefore was the one major power standing in the way of a Northern European hegemony of the Protestant powers.

The basic plan for the final liquidation of the Polish Republic began as early as the latter half of the 1500s, as a strictly military undertaking. First, it seems to have taken the form of a classic and unremitting pincers movement: the Ottoman Turks attacking from the south, the Swedes from the north and the war flotilla of Protestant Holland acting in coordination with the Turkish and Swedish attacks by harassing Polish beachheads in the baltic.

Sweden's Gustavus II Adolphus had an added impetus for his involvement in this effort against Poland. As a brilliant strategist, he surely appreciated the importance of liquidating Poland for the sake of establishing the desired Protestant hegemony. But in a world where royal bloodlines crossed every border and were part of every international initiative, whether friendly or hostile, he had his own dynastic quarrel - an aill-fated one for him, as it turned out - with Poland's King Zygmunt II, who was in fact King of Sweden from 1597 to 1604.

Bloody as they were, these early efforts against Poland came to ruin with the Turkish defeat of 1571 at the naval battle of Lepanto, the second Turkish defeat, at the hands of the Poles, in 1621, and the sudden death of Gustavus II Adolphus in battle, in 1632.

When war alone failed to achieve the aim of the Protestant powers to deliver Poland's territory into the hands of the Protestant allies and eliminate here from the scene as a power, the effort shifted toward a carving up of the territory of the First Republic on the apparently legitimate score of dynastic succession.

While there is no doubt at all that constant wars weakened Poland seriously, it was this "diplomatic" effort - long and complex and with many players involved - that was to prove Poland's undoing. And into the bargain, finally it would set a new pattern for internationally dealings that would reach well into the twentieth century.

Among the many and complex factors in this new assault on Poland were the wide-ranging plans of Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector of the English Republic from 1653 to 1658. Cromwell's foreign policy aimed at a weakening of imperial Spain and at the creation of a grand Protestant alliance between England, Germany, Denmark, Sweden and a Holland freed from Spanish domination.

A second, closely related factor was perhaps the oldest of the secret associations that arose in Germany in the 1600s: the Order of the Palm. The order recruited its members in Germany, Scandinavia and Ottoman Turkey; all three had long since understood that the presence of Pland constituted the gravest obstacle to their mercantile and trading plans. The historical researches of the Polish scholar Jan Konapczynski have rightly pointed to the importance of Cromwell's attempted cooperation with the Order of the Palm. But with or without Cromwell, by the closing years of the 1600s, the order concerned itself seriously with the choice of who would become Poland's elected king.

Given those complex royal bloodlines of Europe, such an idea was far from frivolous or unattainable. For the Order of the Palm included such active and powerful leaders as Swedish Chancellor Axel Gustafsson Oxenstierna, Swedish King Gustavus II Adolphus, and Friedrich Wilhelm, Grand Elector of Brandenburg. Moravian bishop Jan Amos Komensky acted as agent for the order between the Swedes and the Germans. And German philospher Gottfried Leibniz, as secretary of the Alchemist Society of Nuremberg - an affiliate of the Order of the Palm - employed his undoubted talents in favor of getting Palantine Philip Wilhem elected as King of Poland in 1668-69, when the Polish crown did in fact fall vacant. The Leibniz effort failed; but it was a portentous stab at the legalistic dismemberment of Poland.

As the 1600s drew to a close, another effort to take Poland from within, as it were, came much closer to success. Friedrich Augustus I of Saxony was elected King of Poland in 1697. Like the first Piast King, Mieszko I, in 966, and like Jagiello in 1386, Friedrich converted to Roman Catholicism. But in his case, it was no more than a drill to pass muster; for he was and remained a devotee of the "reconstructed" Kabbala, and indulged in so-called cabalistic experiments.

Friedrich's German prime minister, Baron Manteufel, was clearly of the same stripe. A few years later, in fact, in 1728, he created the Masonic Court Lodge in Dresden, with an affiliate Lodge in Berlin. The seal of this Court Lodge was the Rosy Cross - the cross surmounted by a rose; and it counted among its members Friedrich Augustus I himself, and two Prussian kings, Friedrich Wilhelm I and Friedrich Wilhelm II.

Unlike Mieszko and Jagiello, Friedrich Augustus I did not last long as King of Poland. But during his seven-year reign, his foreign policy was directed toward the eventual partitioning of Polan's lands among here neighbors - and effort he continued even after he was deposed, in 1704.

It did not help Poland's position in this new political onslaught from within that she had been continuously at war since 1648. At one stage, she had sustained what contemporary Polish historians called the "Deluge" - a combined invasion of her terriory by Swedes, Brandenburger Germans, Transylvanian Hungarians and Muscovites, all of whome were banking on the support of Cromwell's England and on an internal revolt of Protestants and pro-Protestant Catholics within Poland.

Poland survived the "Deluge", just as she had survived so many wars. But by the opening of the 1700s, she had sustained jover a century of nearly continuous armed conflict. Now an abuse of constitutional prileges by Poles themselves, and a succession of weak and unacceptable rulers - Friedrich Augusts I was but one - brought the country to the condition of the "Sick Man of Europe".

The first half of the 1700s was, as well, a time that witnessed the great

efflorescence of European Masonic Lodges - the true dawning of Accepted Masonry;

and Poland by no means escaped its impact. Undoubtably, in fact, Masonry had been

introduced as an important dimension among Poland's ruling classes by Friedrich Augustus I;

and the influence of Prime Minister Manteufel doubtless accounts for the Prussophile

character of Polish Masonry underlined by some historians.

The first half of the 1700s was, as well, a time that witnessed the great

efflorescence of European Masonic Lodges - the true dawning of Accepted Masonry;

and Poland by no means escaped its impact. Undoubtably, in fact, Masonry had been

introduced as an important dimension among Poland's ruling classes by Friedrich Augustus I;

and the influence of Prime Minister Manteufel doubtless accounts for the Prussophile

character of Polish Masonry underlined by some historians.

This was also the Enlightenment era. Inevitably, therefore, philosophy and science entered the fray; for many brilliant exponents of the new disciplines were also adherents of the principals of Masonry. Human intelligence, as a reflection of and participatioin in the wisdom of the Great Architect of the occultist humanists, was now seen as the infallible element in man's progress.

While the notion of the Great Architect was maintained, the alchemist element of the old humanist associations fell into disrepute and disuse with the onrush of scientific discoveries. The energies of the new ititiates were channeled into more practical ways of attaining their sociopolitical goals.

Much of the symbolism and ceremonial that had been evolved in that earlier prescientific cabalism survived. But Masonic humanism as a living force now relied on uninhibited human inquiry, free from any adjudication - especially on the part of the Church and of religion; for that bedrock anti-Church ideology inherited from the thirteenth-century Italian dissidents remained intact - as the only foundation of human civilization. Catholic beliefs were seen as retrograte, as the great inhibitors of human happiness.

Predictably, such political and philosophical elements involved in Masonry as ideological foundation blocks exacerbated the already virulent hatred of the Roman papacy. And this was true especially in the Catholic heartland countries of France, Belgium, Italy and Spain.

The most powerful and all-directive Masonic Lodge in Europe, for example, was the Grand Orient of France. The anti-Roman and anti-Christian hostility in the Grand Orient became almost legendary. With true Gallic logic, in fact, its participants abolished even the old Masonic oblication to believe in the Great Architect of the Universe. In this step - bold even for Accepted Masons of the Enlightenment era - the French Masons were being very French: ahead of everybody else, and discomfiting in their frankness. Still, it was the Grand Orient type of Masonry that took hold in Catholic countries such as Portugal, Spain and Austria, and in Italy itself.

As early as 1738, Pope Clement XII could see the full georeligious and geopolitical implications of Accepted Masonry, whose Lodges included not only the new and deeply influential intellectual leaders, but the most powerful political personages of the day. Clement condemned Masonry as incompatible with Catholic belief - as indeed it was. And he condemned its secrecy as an unlawful practice that would make possible the subversion of nations and governments.

By then, however, it would appear that the die was all but cast, And

Poland was to become the classic fulfillment of Pope Clement's warning

concerning the subversion of nations and governments.

During the first half of the 1700s, Masonic Lodges - many modeled on the Grand Orient

and on English-Teutonic Masonry - profilerated in Poland like eggs in a henhouse.

According to historians of the stature of Stanislaw Zaleski, Jedrzej Giertych and

Stanislaw Malachowski-Lipicki, some 316 Lodges dotted Poland in the seventy-seven

years between 1738, when Pope Clement issued his condemnation, and 1815, when the

Great Powers of the world agreed at the Congress of Vienna to ratify, under

international law, the then accomplished fact of the obliteration of Poland from

the face of the geopolitical world.

As in every other country, it was not the number of Lodges in Poland, or the

size of their membership - reported by historians as 5,748 - that was the

determining factor in their influence over Poland's fate. Rather, it was as

always the fact that Masonry successfully recruited leading and

influential intellectuals and the politcally powerful members of royalty

and the aristocracy - the "superstructure" of society that Karl Marx and

Friedrich Engels would point to, within a mere thirty-three years after

the Congress of Vienna, as the oppressors of the "working masses".

As in every other country, it was not the number of Lodges in Poland, or the

size of their membership - reported by historians as 5,748 - that was the

determining factor in their influence over Poland's fate. Rather, it was as

always the fact that Masonry successfully recruited leading and

influential intellectuals and the politcally powerful members of royalty

and the aristocracy - the "superstructure" of society that Karl Marx and

Friedrich Engels would point to, within a mere thirty-three years after

the Congress of Vienna, as the oppressors of the "working masses".

The historical track of the founding of important humanist Masonic Lodges in Poland, and that of the three successive land grabs - partitions, they were called - of Polish territory, are compelling in the way that they seem to intertwine.

One of the more important Lodges, Wisniowiec, was founded in 1742 at Volhynia. In Warsaw, four major Lodges - Three Brothers, Dukla, Good Shephard and Virtuous Samaritan - were founded in 1744, 1755, 1758 and 1769 respectively. The Grand Polish Lodge dated from 1769, as well; its doctrinal authority was the Scottish Chapter of St. Andrew, and the Rosicrucian chapter founded in Germany by Poland's former prime minister Manteufel.

Within this stuningly fertile period for Masonry, Poland saw the election of three monarchs - her last as a republic - who ranked among the most ardent promoters of Polish Masonry. Augustus III died in 1763. He was succeeded buy Stanislaw Leszczynski, who died in 1766. He in turn was succeeded by Stanislaw Poniatowski, who outlived the Republic by about three years.

Within that period, as well, Poland was subjected to unremitting invasion, to commercial harassment, to an increasing international isolation, and to what was probably the most crippling influence of all - internal subversion on a wide scale.

Recent studies by scholars demonstrate that during the first two thirds of the eighteenth century, large numbers of the Polish political and intellectual elite were won over to the humanist ideals of Masonry. As a consequence, they willingly collaborated in producing a numbing constitutional paralysis in the First Polish Republic. For clearly, in all their breadth and implications, the Three Pacts of Polishness - the Piast Pact with the Holy See of Rome, the Pact with the Primate Bishop of Interrex, and the Pact with Mary as the Queen of the Kingdom of Poland - were irreconcilable with the securlarizing intent of Masonry. As it happened, sweetly enough for Masonry, the political fortunes of the Holy See were in visible decline all over Europe by this time.

It is more than merely ironic that the first great model of modern democratic government was also the first to fall victim to all the pitfalls that have lately become familiar all over again.

Poland's legislature began to use its ovesight powers to encroach on the powers of the elected head of state. The supreme court followed suit, encroaching onto the domain of the legislature. Representatives began to resort to political ruses to ensure their constant reelection. Democratic liberty was cited as the basis to undermine the moral foundationss on which liberty had been based, and to paralyze government along doctrinaire lines of ideological humanism.

All of these embittering and inhibiting conditions had contributed their generous share to Poland's political decadence and to its internal weakness by the time of Stanislaw Poniatowski took power in 1766 as the third in the line of Polish Masonic kings.

By 1772, Poland was so weakened by wars and international intrigues and corrupt government, that the first partial dismemberment of her territory - the First Partition of Poland - became possible. Russia and Prussia, in alliance with Austria, were the beneficiaries, carving up the first spoils three ways.

At about this time also, there started in Russia and Prussia that process that was to become so familiar: the slandering of everything Polish and the poisoning of the European mind with a dislike that amounted to contempt for Poles, and what remained of Poland.

On the Masonic front in Poland, an intra-Masonic rivalry broke out for predominance in Polish Masonry. After much contention between the English, French and German Masonic authorities, the Royal York Lodge of Berlin won the day. In 1780, it organized a new Polish Lodge, Catherine of the Polish Star, and obtained for it from English authorities a patent as a Grand Provincial Lodge. In 1784, it became the Polish Grand Orient.

By 1790, on the political front, the First Polish Republic had deteriorated into such a helpless condition that it was successfully forced into an unnatural and ultimately deadly alliance with its mortal enemy, Prussia. The Polish-Prussian Pact of 1790 was signed. Its chief architect, Ignacy Potocki, was Grand Master of Polish Masonry. And the conditions of the Pact were such that the succeeding and final two partitionings of Poland were inevitable, in the circumstances.

The final blows fell quickly upon Poland. In 1793, the Second Partition reduced Poland from its original population of 11.5 millioni to about 3.5 million. In effect, however, it was merely a prelude to the Third Partition. By the end of 1795, the long struggle to take Poland from the Poles was over. The last freely elected chief executive of the First Polish Republic, King Stanislaw, was forced to abdicate by Russia, Prussia and Austria. Triumphant at last, the Three Powers proceeded to divide the cadaver of Poland between them.

In a great foreshadowing of things to come in the twentieth century, Russia grabbed all of Lithuania and the Ukraine, with a combined population of some 1.5 million people. Prussia seized Mazovia, with Warsaw at its center - a million people more. And Austria made off with the Krakow region and its one million people.

With Poland's extinction complete, all that remained to accomplish was the eradication

of the name of Poland from the map of Europe; and the obliteration of the memory of the

Polish presence in Europe. It was precisely to that declared and openly pursued policy

that the Three Powers made a joint commitment.

Among the ordinary Polish people, now forcibly parceled out among other populations,

hope lingered that the tripartite decision to liquidate their country would be reversed.

That hope was given an enormous boost by the sudden and stunning military successes of France's

Napoleon Bonaparte. Beginning in 1796 - only a year after the Third Partition of Poland -

his resounding victories against all comers threw all the powers of Europe into violent

flux; and, in geopolitical terms, it made sense for Poles to take hope.

In spite of his extraordinary genius as a military strategist, however, and in spite of his grandiose imperial ambitions, Napoleon was and remained a man of the French Revolution. When he looked at a map of Europe, he saw only lands to conquer, and the contours of military campaigns by which to do it. He never once grasped the geopolitical forces at work in Europe.

As a consequence, he attacked where he should have defended and befriended - his natural

allies were in Poland, Russia, Spain, and Italy; and with them, he could have beaten the

northern alliance ranged against him. Further, he preserved what he should have destroyed -

Prussia, for example, after soundly defeating it at the battle of Jena. And finally,

he neglected to build strength where he needed it. A divided Poland was the most

pathetic example of that neglect; for while he did create the duchy of Warsaw, it was no

more than a sorry caricature of Poland, and neither restored the Polish nation-state nor

constituted anything that could be of help to Bonaparte.

As a consequence, he attacked where he should have defended and befriended - his natural

allies were in Poland, Russia, Spain, and Italy; and with them, he could have beaten the

northern alliance ranged against him. Further, he preserved what he should have destroyed -

Prussia, for example, after soundly defeating it at the battle of Jena. And finally,

he neglected to build strength where he needed it. A divided Poland was the most

pathetic example of that neglect; for while he did create the duchy of Warsaw, it was no

more than a sorry caricature of Poland, and neither restored the Polish nation-state nor

constituted anything that could be of help to Bonaparte.

At the end, the whole world wanted to be done with the "little corporal", for, as long as he held strong, there would be no peace in Europe. After rampaging around the continent for almost twenty years, Napoleon was definitively eliminated. Banished to the remote island of St. Helena in June 1815, he died there on May 5, 1821.

Even then however, Bonapartism was to produce perhaps the most important of its enduring consequences: Raw power, and the preponderance of such power, was thenceforward accepted as the international yardstick for the arrangement of human affairs.

The victorious powers of Europe assembled at Vienna in September of 1814 to rearrange the map of their continent. Europe would never again be as it was before Napoleon. At the Congress of Vienna, there was neither a religious principle nor any kind of moral suasion for the decisions made. Certainly, Europe was not even remotely ready for anything for anything resembling the geopolitical principal expressed fully four hundred years before in Poland's Act of Union, by which powers agreed to unite and to govern themselves on the basis of that divine love through which "laws are established, kingdoms are maintained, cities are set in order, and the well-being of State is brought to the highest level."

Quite the contrary, the Congress of Vienna ws the first international meeting of European powers where the rule of thumb was to divide the spoils of war. Aside from the aim of preventing a recurrence of the danger all had been subjected to by Bonaparte, the purpose of the victorious parties was to balance raw power among themselves. And in that, it provided the model that would be followed by the Versailles Conference of 1918, ane by the Yalta and Potsdam conferences at the end of World War II

The historical track of the geopolitical involvments of Masonry and the demise of Poland appears to have continued; for historians have pointed out the Masonic identity of the main movers at the Congress of Vienna - Metternich for Austria, Castlereagh for Britain, Czartoryski, a Pole, and the Russian Czar.

Ercole Cardinal Consalvi as papal secretary represented the interests of the Pope. But his involvement was little more than what might be called an act of presence, required only by the fact that participants saw the Papal States as part of the world order they wanted to restore after the tumult caused by Bonaparte. In fact, "Holy See" as an internationally recognized papal title originated in the agreements of the Vienna Congress. Beyond that, however, the Cardinal's presence had little more effect than the nonpresence of any papal representative at the Versailles Conference a century later, when it was explicitly agreed in advance by the victors of World War I that the Holy See would have no say in the terms that dictated the end of that war with Germany.

In the circumstances that prevailed at Vienna in 1814-15, then, whatever hope there might have been for reversing the Third Partition of Poland evaporated. In its balance-of-power arrangements, the Congress ratified the tripartite mutilation of Poland, and the continued crucifixion of the Polish people as a nation, by what was asserted and maintained to be international law.

The First Polish Republic, with its constitutional monarchy and its spendid democratic institutions, was to die. Poles as a nation of people in Europe officially ceased to exist. Poland as a geoplitical entity was effectively to disappear from all the maps of Europe. For Poland - people and country - death and entombment was the decision of the Congress.

In the flush of their victory, the participants at the Congress of Vienna suffered from a lack of prescience at least as severe and costly as Napoleon's lack of geopolitical acumen. As members of the ancien regime of crowned heads and of autocratic and privleged landed aristocracy, they failed to appreciate yet another legacy Napoleon had left them.

As a child of the Revolution, Bonaparte had sown the seeds of dissolution all over Europe. He had smashed the hard surface imposed on European peoples by the ancien regime. He had shown its flaws, demonstrated its weaknesses, proved it was not perpetual. It was now a matter of time before the people - as distinct from the traditional supersturcture of society - would clamber out and demand their place in the sun. It was, in fact, a mere matter of thrty-three years before Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels would publish The Communist Manifesto.

By then, however, Europe had fully deprived itself not only of the Polish democratic models for freedom of political and religious rights in a European context. It had deprived itself as well of the land that had stood strategically for a thousand years as Central Europe's strong and vibrant northern bulwark.

Given that the internationally agreed aim, as recorded in the sentiments of the Congress of Vienna, was to inculcate the persuasion that "nothing good can come out of Poland," and "nothing good and acceptable must be ascribed to Poland and its Poles," the question of what to do about Polish Masonry became an intersting logistical problem.

In essence, the difficulty was neatly finessed. The Polish Grand Orient, which dated from the period between the First and Second Partitions of Poland, was dissolved on September 24, 1824, by order of Czar Alexander I. All other Lodges in the territories formerly known as Poland - the Congress Kingdom, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, parts of the Russian Empire and the Free City of Krakow - were likewise dissolved. German Masonic organizations took over the Lodges that remained in Poznania. And the liquidation of Polish Masonry was completed when the Polish Lodge known as "Piast Beneath the Three Sarmatian Columns," together with the German Lodge Zur Standhaftigkeit, or Endurance, was merged into a new German Lodge - Tempel der Eintracht, or Temple of Unity - to which the Prussian government gave full support, as it did to all other German Lodges in its territory.

It was only after the Polish insurrection of 1831 that purely Polish Lodges raised their heads

tentatively but identifiably once again - in Besancon and Avignon, France, in 1832; in London

(the Polish National Lodge) in 1846; and in a new Lodge in the famous Polish Armed Forces

School in Cuneo, Italy, in 1862. Otherwise, even Polish Masonry would have to wait

until the beginning of the twentieth century for its revival.

If it is to be said that the ultimate aim of Poland's enemies wsa the obliteration of the

Roman papacy as a georeligious and geopolitical force in Europe, then it must be said as well that

the flourishing Freemasonry of the Enlightenment accomplished at least two major victories

over the Roman Catholic Church on both counts.

In 1773, the year following the First Partiion of Poland, and a time when Rome found tiself weakened in the traditional political sense, the suppression of the Society of Jesus was achieved under the architectural direction, as one might say, of dedicated Masons - the Marquis de Pombal, royal adviser in imperial Portugal: Count de Aranda, royal adviser in imperial Spain; the Duc de Choiseul and Minister de Tillot in imperial France; Prince von Kaunitz and Gerard von Swieten at the imperial court of Maria Theresa in Habsburg Austria. With that coup, the Roman papacy was deprived of an inernationally distributed, highly trained, deeply respected and maddeningly resourceful battalion of papal loyalists. Their suppression at a critical moment removed the most dedicated offensive and defenseive insturment ever placed in the hands of the Roman pontiffs. It was a loss whose consequences were to be felt by the papacy into the present day.

The second achievement - liquidation of Poland in the same general period - was a blow in the very same direction as far as its specific impact on the papacy was concerned. For the destruction of Poland as a nationstate stripped Roman Catholicism as a geopolitical force of a northern bulwark and of a powerful Catholic influence in the international affairs of Central Europe. And it stripped Roman Catholicism as a georeligious force of a powerfully radiant center for Catholic doctrine.

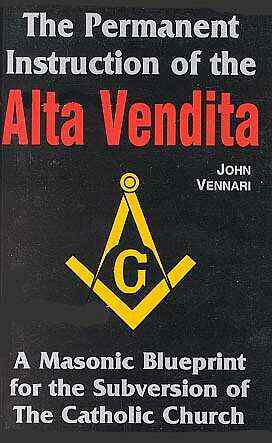

Some idea of the confessional enmity entertained by Masonry for the Roman papacy can be gleaned from the Permanent Instruction drawn up a few years after the Congress of Vienna, in 1819-20, by the French, Austrian, German and Italian Grand Masters of the Lodges:

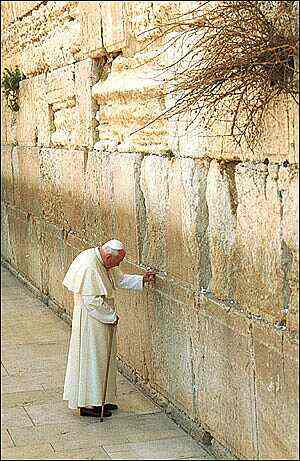

... we must turn our attention to an ideal that has always been of concern to men aspiring to the regeneration of all mankind ... the liberation of the entire world and the establishment of the republic of brotherhood and world peace. ... among the many remedies, there is one which we must never forget: ... the total annihilation of Catholicism and even of Christianity. ... What we must wait for is a pope suitable to our purposes ... because, with such a pope, we could effectively crush the Rock on which God built his Church. ... Seek a pope fitting our description ... induce the clergy to march under your banner in the belief that they are marching under the papal banner ... make the younger, secular clergy, and even the religious, receptive to our doctrines. Within a few years, this same younger clergy will, of necessity, occupy responsible positions. ... Some will be called upon to elect a future pope, like most of his contemporaries, will be influenced by those ... humanitarian principals which we are now circulating. ... The medieval alchemists lost both time and money to realize the dream of the "Philosopher's Stone." ... The dream of the secret societies [to have a pope as their ally] will be made real for the very simple reason that it is founded on human passions...The Masons, it would seem, had stolen a march on Antonio Gramsci and the brilliant plan he proposed to his Marxist brothers for the extinction of Roman Catholicism as the central force impeding the de-Christianization of the Western mind. For both Marxists and Masons, however different and opposed they may be politically, are at one in locating all of man's hopes and happiness in a this-wordly setting, without any intervention of a divine action coming from outside the cosmos and without appointing an otherworldly life as the goal of all human life and endeavor. Marxism and Masonry transcend, both of them, individuals and nations and human years and centuries. But it is rather an all-inclusive embrace, holding all close to the stuff and matter of the cosmos, not in any way lifting the heart and soul to a transhuman love and beauty beyond the furthest limit of dumb and dead matter.

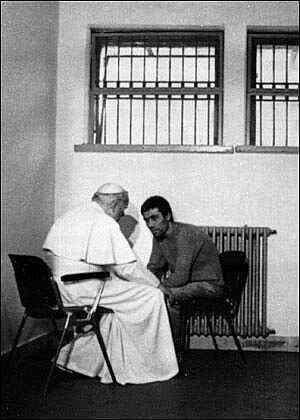

There are similar and disturbing echoes of these extreme policies in the activities of the superforce and the anti-Church faced by Pope John Paul II today, as well as in the statements of some who call themselves "progressive Catholics." For all of these elements of influence in today's Roman Church wish to carry on with a new ecclesiology that would in effect eliminate the Catholic exercise of the Petrine Office. But in 1820, the actual possibllity that such an agenda might be accomplished was still over a century away. Today, it is the ongoing policy of John Paul's intra-Church enemies.

Meanwhile, the commitment to obliterate Poland and its Three Pacts of Polishness, and to see that "nothing good and acceptable must be ascribed to Poland and its Poles," was carried to outlandish lengths in particularly important instances.

One curious and instructive case in point touched the papacy itself, a little more than eighty years after the writing of the Permanent Instruction was completed, and a little less than eighty years before the 1978 election of Pope John Paul II. It concerned the village mailman in the Italian town of Riese in Upper Venetia, one Giovanni Battista Sarto by name, and his wife, Margherita, a seamstress.

Sarto had been born Jan Krawiec in Wielkopolska, Poland. When his part of the country fell into Prussia's hands, Sarto found political asylum in Italy, first in Godero, near Treviso, and finallyin Riese, where he earned a ducat a day delivering the mail to the townfolk.

On June 2, 1835, a son was born to the Sartos, and they baptized him Guiseppe Melchiorre Sarto. The boy, "Pepi" to his family, was schooled in Castelfranco and Asolo. As a young man in 1858 he was ordained a priest. As a middle-aged man in 1884 he bame Bishop of Mantua. And as he was getting on a bit in age in 1893, he was nominated cardinal an promoted to the See of Venice.

Following the death of Pope Leo XIII on July 20, 1903, the papal Conclave narrowly

avoided fulfilling he dream of the Permanent Instruction and electing

Mariano Cardinal Rampolla del Tindaro - the Vatican Secretary of State and an

inducted member of the Masonic Lodge - as Pope and Vicar of Christ. In fact,

Rampolla did actually receive the required number of votes. But Jan Cardinal

Puzyna of Krakow - which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire - exercised

the veto power enjoyed at that moment by His Imperial Master, Franz Joseph of Austria.

Franz Joseph knew of Rampolla's Masonic identity, but he probably had as many

politco-financial as religious reasons for excluding Rampolla from the Roman See.

Following the death of Pope Leo XIII on July 20, 1903, the papal Conclave narrowly

avoided fulfilling he dream of the Permanent Instruction and electing

Mariano Cardinal Rampolla del Tindaro - the Vatican Secretary of State and an

inducted member of the Masonic Lodge - as Pope and Vicar of Christ. In fact,

Rampolla did actually receive the required number of votes. But Jan Cardinal

Puzyna of Krakow - which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire - exercised

the veto power enjoyed at that moment by His Imperial Master, Franz Joseph of Austria.

Franz Joseph knew of Rampolla's Masonic identity, but he probably had as many

politco-financial as religious reasons for excluding Rampolla from the Roman See.

It took seven more voting sessions before the Cardinal Electors chose the sixty-eight-year-old Giuseppe Melchiorre Cardinal Sarto of Venice, who chose the papal name of Piux X.

On Sarto's election as Pope, the scramble of high officials in the Austrian monarchy was almost as comic as it was tragic, as they scurried to destroy all certificates and records that might reveal the Polish origins of Piux X. In accordance with the expressed sentiments, aims and intentions of the Congress of Vienna, nothing as good as pope could come out of Poland.

At least one trace of Sarto's Polish heritage did survive, however, in spite of all the efforts to the contrary. The elder Sarto's original surname, Krawiec, is also the Polish word for "tailor". That, in fact, was the reason he chose Sarto as his Italian surname; for sarto is the Italian word for "tailor."

Still, so vigorously was the death and entombment of Poland and Polishness pursued that grown men of presumed probity swarmed like carpenter ants to devour all the official records in Krakow and in Italy, as well, that might reveal the Polish origins of the Krawiec-Sarto family.

Chapter 28

The Keys Of This Blood

Simon and Shuster

New York, NY

1990

About Malchi Martin the critics have written: "He is the most fascinating writer

in the religous field today" (The Sunday Houston Chronicle). "He is one

of the people most knowledgeable about the inner workings of the Vatican currently

writing about the Church" (San Jose Mercury News).

About Malchi Martin the critics have written: "He is the most fascinating writer

in the religous field today" (The Sunday Houston Chronicle). "He is one

of the people most knowledgeable about the inner workings of the Vatican currently

writing about the Church" (San Jose Mercury News).

A former Jesuit and professor at the Vatican's Pontifical Biblical Institute, Martin is the author of the bestsellers The Jesuits, The Final Conclave, and Hostage to the Devil.

The 1970's movie The Exorcist was based on Father Martin, a duty

he performed for the Church for many years.

Further Reading: